Hyperrealism Magazine Written Interview

Posted By: Hyperrealism Magazine - 20 Dec, 2020

- Your works mainly depict suggestive landscapes and figures with dramatic tones. The result is extremely accurate and impressive, tell us about your personal working method to achieve the complexity of your paintings.

Early on, as I was developing my oil technique I was also interested the media of watercolour whose technique is the antithesis of oils in that you are working from light to dark retaining the white of the paper for the lighter tones and highlights. With this knowledge when blocking in the oil painting, I employ a similar technique thinning down the more transparent pigment so the white of the canvas was used to roughly define the tonal variations. Over this I define the forms in the painter more by using small round watercolour brushes to paint in the shadows. Once this is dry, I proceed to put in the highlights and by going back and forward with the shadows and highlights the painting is completed by ending this process with the lighter tones in the painting. This is the technique in a nutshell however there are other techniques involved like glazing whole sections of the painting with a transparent pigment if I feel it is too light.

The paintings are developed from occasionally a single photograph but more often several photographs cut and pasted. In the past, this was developed into a drawing which was then projected onto the canvas however to speed this process up in recent times I have employed Photoshop to cut and paste a rough image which I then alter during the painting process.

- Your paintings, in addition to being technically virtuous, also have a social purpose: describe us your themes and the meaning you give to your art.

After developing my technique to the realistic degree I was happy with (which took about 5 years during my early 20s), I felt that painting portraits and landscapes were okay but I needed to be further challenged by taking the paintings to another level by creating some kind of narrative to them. I think I have always been something of a futurist and so I started studying human behaviour and other human related issues such as environmentalism. Avoiding currently topical subjects I have tried to create a narrative that is a generalisation of the causes of these various issues, in particular the conflict or tension between opposing forces and the impossibility of reconciling this polemic. In the works that deal with the environment the narrative is a little more obvious but I also try to give the paintings a title that might act as a key to a greater understanding of what I am trying to say.

- We can say that each of your paintings is unique in composition and meaning. Are there any works that you consider most important to you?

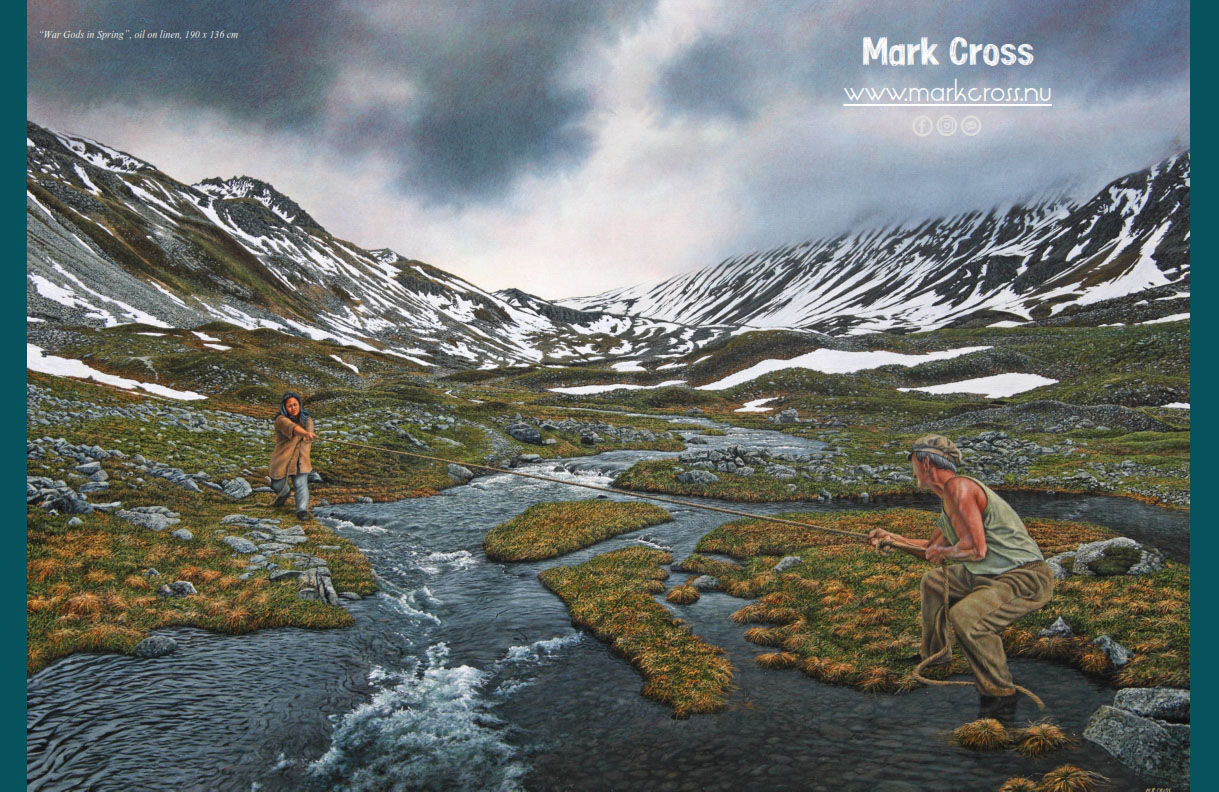

Although in the unpeopled coastal and landscapes there is nearly always a subtle environmental narrative, by adding figures to them it takes the narrative to another level and even more so with the multi-figured works. My fascination with the properties of water has also informed my work over the years and when combined with the human figure to create a story, I find these paintings the most challenging and therefore, with a few exceptions, tend to work the best for me.

- How has the place where you live influenced your artistic and philosophical research?

I have lived on an Island, one of the smallest sovereign nations on earth off and on for 42 years. Early on I started to view the island as a microcosm of the whole world both in terms of its physical environment and its social zeitgeist. With a fluctuating population of around only 1600 it is easy to witness the foibles that plague humanity on a global scale. For example, while there are no wars, conflict exists scaled down and it does exist though usually kept in check by tacit social contract. Likewise, environmental issues are very real though scaled right down and there is a constant effort to keep this aspect in check in an ever increasing consumer culture. The landscapes of the places I have travelled always find their way into my painting but because I am here most of the time it stands to reason that elements of the Niue landscape particularly the coastal cliffs and clear water have not only provided a stage for my vignettes but have actually informed some of my ideas.

- It is difficult to define art, and over time the conception of art has changed, seen by some as a purely aesthetic and decorative factor and by others as a powerful means of expression for important causes. According to your point of view, can art represent a fundamental weapon for social issues? How could a work be able to shake the observer's conscience?

In my idealistic youth I believed art could change the world more than merely reflect it. I’m not so sure now however I think if one has the passion, knowledge and the tools to attempt it, they should not hold back. I have always believed that realism is a powerful medium to attempt change due to its democratic nature. On a superficial level most people are in awe of the craftmanship but having been drawn into it for that reason, many may go beyond that superficiality and become interested in the narrative behind it. I think shock value can shake the audience’s conscience but I have consciously avoided that believing it too ephemeral and by employing a more subtle message, the image may resonate in the person’s memory for much longer.

- Your artistic intervention in your geographical area is not limited only to the pictorial production, in fact, you have established a sculpture park in the rainforest near Niue and, together with your wife and other artists, you have contributed to the creation of the itinerant installation entitled Shrine to Abundance. Tell us something about these important side projects.

Yes, art is fundamentally a urban occupation and when returning to Niue in 1995 after being mainly in Auckland, New Zealand for 12 years I asked the question, why should that be? The other question was if artists wanted to live in their homeland why should they be discriminated against just because of some ill-conceived stigma of backwardness. There were several such Niuean artists living in Niue when I returned, artists who were well versed in conceptual art and were drawn to it, but because they wanted to isolate themselves in the homeland they had no hope of being recognised in the clicky urban art industry. So first of all, we got to work establishing the sculpture park but more importantly we mounted a group show of these unknown, homeland based artists in Auckland with a gallery I had worked with. This was well received and drew the attention of a curator from the Tjibaou Cultural Centre in Noumea, New Caledonia who was also working with the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane Australia. As a consequence of this I was asked to come up with a collective concept which resulted in the creation of the Tulana Mahu, Shrine to Abundance, situated inside a shipping container. This was created in Niue and travelled to Brisbane, Sydney, Cook Islands, Auckland, Palmerston North (NZ) and back to Niue. Sadly, as is the nature of shipping containers, it began to leak before we had a chance to put a roof over it. The container however has been reinvented and now having a roof it has a more pragmatic functionality as a workshop that has more equipment to aid the development of the Hikulagi Sculpture Park, 2 km south of our village of Liku. This project is ongoing though most of the local artists have now left for the City or died, the spirit of the project is still strong. An important aspect of it is public participation whereby the two major sculptures there grow like trees with the audience adding their discarded consumer waste to the sculptures. There is a natural impulse for most humans to do this to leave their mark somewhere especially if environmental issues are the theme.

The modest commercial success of my paintings has allowed me to venture out into other less profitable media. The pedantic and time-consuming nature of the realist’s craft negates a lot of social interaction. There is a lot of solitude involved. I am by nature a social person, so I have always tried to balance my solitude with artistic collaboration.

- Unfortunately, we will remember this 2020 as a terrible year, with the global forced quarantine. How is the situation in your country and how did you live these periods?

In February I was travelling around in the South Island, New Zealand and we had vague news that there was a potential pandemic out there. I’d already booked a ticket to Rarotonga in the Cook Islands on March 12th for a week. It was during that week when the reality started to sink in and I ended up flying back to Auckland on one on the last scheduled flights before their lockdown. From there my plan was to get on to the last scheduled flight back to Niue a day later. I made it home though was under home isolation for two weeks with health professionals checking me for symptoms every second day. That didn’t inconvenience me at as I needed to clean up my studio and garden, plant some seeds and start a painting after being away from my Niue studio for nearly 3 months.

Niue hasn’t had any infection due to tight controls at our border. It has though, affected my wife Ahi’s, gallery business because that was 98% reliant on tourists. We do sell un-numbered reproductions of my paintings in this gallery along with other local artists’ work.

With no tourists we are adapting, thinking local in terms of the distribution of money coming into the country from New Zealand aid. I have an international waiting list of people interested in my paintings however production has been slow. There has been a spirit on the island toward self-sufficiency especially in regard to food security and I have been a part of this by expanding my gardening capacity. There has been a strong movement back toward exchanging goods and services while money has been tight. Perhaps this will be a good thing that has come out of the pandemic.

- What are you projects for the next future?

Well we’ll try to interest some environmental artists in creating their own sight specific work at the Hikulagi Sculpture Park. Though funding is an issue, there might be someone out there beyond our Oceanic region that might like this idea.

Where painting is concerned, I am trying to formulate a dramatic fictitious event of a group of people, a small crowd of women, men and children hauling tons of fishing detritus, and jetsam out of our coastal waters. Detritus caused by the foreign fishing industry both legal and illegal. It will also be a comment on the dwindling pelagic fish stocks in the world’s oceans. At 2 by 1.6 metres such a painting will prove challenging.

November 2020

Devolution

Gyre Votex Jetsam Collection

Terra Sarcoma

Related Posts

Sienna Palette

"Despite the title, Sienna Palette, the Paintings by Mark Cross at the Pierre Peeters Gallery are tightly governed by the concern for a magic reali...

Sheep Country at Real Gallery by Adam Gifford

The devastation of Niue by Cyclone Heta in January last year sparked a change of course for painter Mark Cross, a long-time resident of the island. After more than a de...

INTRODUCTION TO EXILES IN PARADISE, 14-28 NOVEMBER 2003

It was in April 2001 while viewing the masterpiece, ‘Tangaloa’ in a local private collection that I was first introduced to Mark Cross. Indeed this was an honora...